It is widely accepted that the prime goal of management is to maximize shareholder value. But the road to delivering superior returns is not always clear, for a few reasons.

- Metrics. Corporate managers often perceive that managing to achieve competitive advantage is hard to balance with the demands of the stock market. Which financial metrics effectively straddle the desires of product markets with those of the capital markets? How are those metrics linked to executive compensation? Here it is necessary to have a firm grasp of what competitive advantage is and how the market reflects it.

- Method. Assuming that financial value drivers are properly identified, it is still critical to figure out how to position the business to gain a competitive advantage. Which market segments should be addressed? What customer characteristics are required to generate profitable sales? How are products or services delivered optimally? Addressing these questions is the essence of strategy.

- Market. Managers and investors are not always clear how prices are set in the stock market. Is value determined by earnings growth? Sales gains? Cash flow improvement? These questions require a clear understanding of how capital markets work.

The facts are that competitive advantage, strategy and capital market valuations are intertwined.

The key findings in valuation theory are:

- The spread between return on invested capital ROIC and the cost of capital WACC (defined as "ROIC– WACC") is a reasonable starting point for estimating economic value creation. The stock market efficiently reflects this spread in stock prices. Correlation analysis shows that high ROIC–WACC-spread businesses are rewarded with the high market values for a given growth rate. This suggests that companies should seek attractive returns first and growth second.

- ROIC–WACC spreads consistently form a cascade pattern ranging from value creators to value destroyers. This spells opportunity, because it shows that satisfactory returns are often achievable irrespective of where a company is domiciled or what industry it is in.

- The key to a company’s ability to generate excess returns is the strategy it pursues. Companies must understand where and how they create value. Notably, it is often the company that understands where it does not have an advantage that does well. More directly, strategy matters.

It is important to define two key terms: competitive advantage and strategy. Strategy (including formulation and execution) is the stepping stone to capturing a competitive advantage. Sustainability of competitive advantage requires constant evolution and prudent capital allocation.

Competitive Advantage

- Competitive advantage exists when a company’s sales are greater than its total costs, including the opportunity cost of capital. One measure of such returns is a positive ROIC–WACC spread.

- It should be stressed that competitive advantage is not a qualitative, but rather a quantitative, issue. By definition, a business with a competitive advantage either earns, or promises to earn, returns on capital in excess of the cost of capital.

- Further, competitive advantage must be viewed in absolute, not relative terms. A business that earns higher returns than its peers do, but that does not earn its cost of capital, can be said to have a comparative advantage, not a competitive advantage.

- A company can gain competitive advantage in a number of ways. For example, it can offer a product or service that customers perceive to have superior value, hence garnering a premium price. Alternatively, a company can achieve a lower cost position than its competition, allowing it to glean excess returns.

- The ability to generate positive ROIC–WACC spreads also relates to the structure of the industry in which a company competes. External factors—such as the buying power of customers or the leverage of suppliers—combine with internal factors—including the intensity of rivalry—to define industry structure.

- While some management teams often say they participate in an industry that is structurally poor, the evidence shows that industry structure is not the defining factor in value creation. Ultimately, a company’s ability to generate excess returns comes from the activities a company pursues and how those activities fit together and reinforce one another.

Strategy

- A successful strategy is one that allows a company to capture a competitive advantage. Porter defines strategy as “the creation of a unique and valuable position, involving a different set of activities”. He stresses that operational effectiveness represents excellence in individual activities while strategy is the appropriate combination of activities.

- Strategic positions come in a number of forms. A variety-based position is when a company produces a subset of an industry’s products or services. When a company serves the needs of a particular group of customers, it is pursuing a needs based position. Finally, an access-based position relies on segmentation of customers by access channel.

- Porter argues that strategic positions are not sustainable unless clear trade-offs are made with other positions. Trade-offs are necessary because of potential inconsistencies in image, the difficulty of executing within multiple positions and limits on management resources.

- Strategic failure often comes from an inability to choose the correct strategic position. Managers may be lured to expand their positions in the name of growth.

An evaluation of company returns (as in the following example) always results in a finding that within a company’s portfolio of businesses there will always be a mix of attractive and unattractive operations. Management can always work to improve returns within company (through asset purchases/sales, improved positioning); help improve industry returns (through intelligent use of game theory and signalling); and, hence, improve the overall economy.

Completing an internal review of ROIC–WACC spreads is important however the more pressing issue is whether or not these spreads are reflected in stock price valuation.

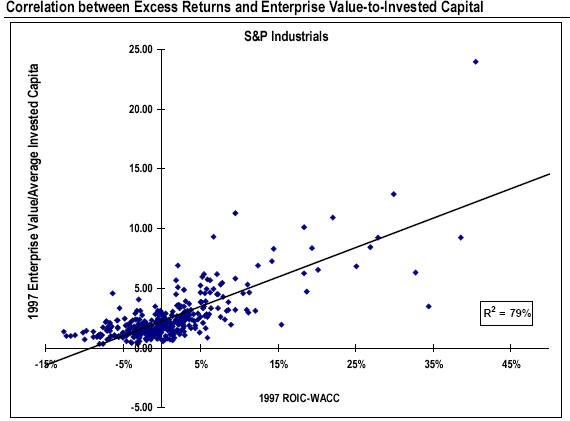

CSFB tested this using regression analysis. The independent variable is the ROIC–WACC spread and the dependent variable is firm value (market value of equity and debt) divided by invested capital. Economic theory suggests that businesses earning above-cost-of-capital returns trade at a firm value to invested capital ratio in excess of one. Further, the higher ROIC–WACC spread—holding growth constant—the higher the warranted firm value/invested capital multiple. Their data support the economic theory.

The study showed the S&P Industrials had an r squared of 79% (a high correlation) that is the market recognizes and rewards positive economic returns.

Thus the link between the stock market, competitive advantage and the strategy can be easily seen. Strategy is the process that allows a company to achieve a competitive advantage. Competitive advantage is the ability to generate returns on capital in excess of the cost of capital. The stock market efficiently reflects excess returns.

The key messages for corporate managers and the investors that evaluate them:

- Economic value creation should always be the guiding light for management decisions. In free markets, above-average gains in shareholder value are generally a sign that collective corporate resources—both financial and non-financial—are being allocated effectively. The further fact that the stock market efficiently capitalizes value creation lends further credence to the importance of managing for value.

- Growth should always be a second order consideration behind value creation. Managers often assume that earnings growth is synonymous with value growth. However, this perspective is not supported by the empirical data—there are projects that add to accounting earnings while detracting from shareholder value. Correct prioritization of value creation/growth objectives allows managers to avoid capital allocation mistakes. This task is further complicated by the reality that many compensation schemes disproportionately reward growth versus value creation.

- A company can create shareholder value if it invests below the average ROIC but above WACC as long as such investments meet or exceed market expectations. But managers must be aware that the stock market is forward-looking. As a result, some projects may be value creating (net present value positive) but may disappoint the market, leading to a lower stock price.

- ROIC–WACC spreads should be used with some caution. This metric does offer a reasonable snapshot of the past performance and can serve as a good proxy for expectations. However, the calculation is based on accumulated sunk costs (invested capital) and can be affected by the timing of capital expenditures and chosen the depreciation method. For this reason, you should use the NPV positive rule to the use of ROIC–WACC spreads.

- In stock market valuation, both excess returns and duration of excess returns are important. The latter notion is often called “sustainable competitive advantage.” Consistently generating excess returns is management’s greatest challenge.

- Strategy is the key. Excess returns can be earned even in the worst industry groups. What separates the winners from the losers is how they organize their activities. Managers of businesses that generate sub-par returns should constantly rethink the activities they pursue.